At COP30, civil society stepped into real, not symbolic, leadership

After several conferences shaped by restrictions and tensions between governments and social movements, this COP had active voices in the discussions from grassroots organizations, Indigenous peoples,...

An observer who attended COP30 in Belém, Brazil, shares her perspective on the conference

Originally published on Global Voices

Global March during COP30, in Belém, Brazil. Photo by Bruno Peres/Agência Brasil, used with permission.

The author, Isabela Carvalho, is the director of knowledge at Ashoka, a global network of social entrepreneurs, and part of the board of directors of the think tank Washington Brazil Office (WBO). She attended the United Nations Climate Change Conference as a civil society delegate.

For those who walked through it, COP30, the United Nations Climate Change Conference held in 2025 in Belém, Pará state, in the Brazilian Amazon, was marked by the strong presence of organized civil society in the official spaces, parallel events, and in the streets.

After several conferences marked by restrictions and tensions between governments and social movements, the Brazilian edition created space for grassroots organizations, urban collectives, Indigenous peoples, “quilombola” communities (descendants of enslaved Africans organized in traditional territories), and “ribeirinhos” (traditional communities living near rivers) to make their agendas visible across the city.

Hosting the conference in Brazil likely contributed to this environment, at a moment when the participation of social groups is again gaining institutional weight. Belém also sets its own rhythm, since it is impossible to be here without noticing the communities that have long carried the direct impacts of environmental policies and who now feel legitimized to speak in the first person.

Belém is an Amazon capital of 1.3 million people, located at the mouth of the Guamá River, near its encounter with the Amazon River, one of the largest in the world. Traveling by river marks daily life, connecting Indigenous, quilombola, and riverine communities to the city. This diversity is visible in the food, public markets, languages, and sounds, and helps explain the strength of territorial voices at this year’s COP.

The People’s Summit played a central role in this process. It worked as a political space to articulate positions and build consensus around collective demands that often do not reach the formal negotiations, led by social movements, urban collectives, and local and Indigenous communities working on climate and territorial justice.

At the closing, representatives delivered a letter outlining the main demands of these movements to COP officials and members of the Brazilian government.

The People’s Summit made history at Amazon’s COP, with country, forests and city communities from diverse territories around the world. This Friday, the summit continues its program with interactions, positioning people as a factor of resolution in global crisis.

The contrast with past COPs is clear. In Glasgow, Scotland, in 2021, participation by civil society from the Global South was constrained by costs, quarantines, and visa delays. In Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, the following year, government restrictions made protests almost impossible. In Dubai, United Arab Emirates, in 2023, the dominant presence of the fossil fuel sector reduced the political space for social movements. Last year, in Baku, Azerbaijan, despite progress in climate finance, civil society had limited visibility.

In Belém, there was a sense of reconnection with the streets and with the idea that a climate conference can go beyond government negotiations.

“The demands appeared in a well-articulated way, showing that society is watching and creating concrete solutions,” said Rafael Murta Reis, director of Ashoka Brazil, a global social organization of which I am also a part.

Indigenous voices

Indigenous people at the Global March during COP 30. Photo by Bruno Peres/Agência Brasil, used with permission.

Indigenous participation was also a major highlight. Some of these voices arrived by river: the Yaku Mama Flotilla, made up of more than 60 Indigenous leaders from Brazil and neighboring Amazon countries, traveled 3,000 kilometers (1,864 miles) for over a month from Ecuador, Peru, and Colombia to Belém. In boats and canoes, the journey added a symbolic dimension to the climate debate on rivers and territories.

According to COP organizers, more than 900 Indigenous participants were accredited for the official negotiation zone (the Blue Zone), a significant increase over the previous record of just over 300. The final text of the conference included an important political mark by recognizing that Indigenous territorial rights are part of the global climate strategy, a long-standing demand of Indigenous movements.

Panel: Kuntari Katu Program, at the COP 30 Green Zone. Photo by Isabela Carvalho, used with permission.

“Brazil now has a new Indigenous peoples’ diplomacy,” said Lucas Marubo, of the Marubo people in the border region between Brazil, Peru, and Colombia, during a panel in the COP30’s Green Zone. “We leave the COP30 with the same certainty we walked in with: any mechanism, funding or agreement only has legitimacy if it is anchored in Indigenous territorial sovereignty. Our vigilance continues because we are not fighting for profit, we are fighting for life.” Lucas is part of the Kuntari Katu Program, a Brazilian government initiative that prepares Indigenous leaders for international conferences.

“Our main urgencies are securing our territories as the basis for adaptation, strengthening food sovereignty and care for our rivers, supporting community infrastructure created for these times, strengthening adaptation plans built by us, and recognizing that health, traditional knowledge, and well-being are also adaptation policies. All of this is already being done by our peoples, with very little [resources],” said Josimara Baré, of the Baré people of the Rio Negro region, on the border between Brazil and Venezuela, also part of Kuntari Katu.

The tone in the March and in the rooms

Young people at the Global March, in Belém, at COP 30, announce their demands. Photo by Bruno Peres/Agência Brasil, used with permission.

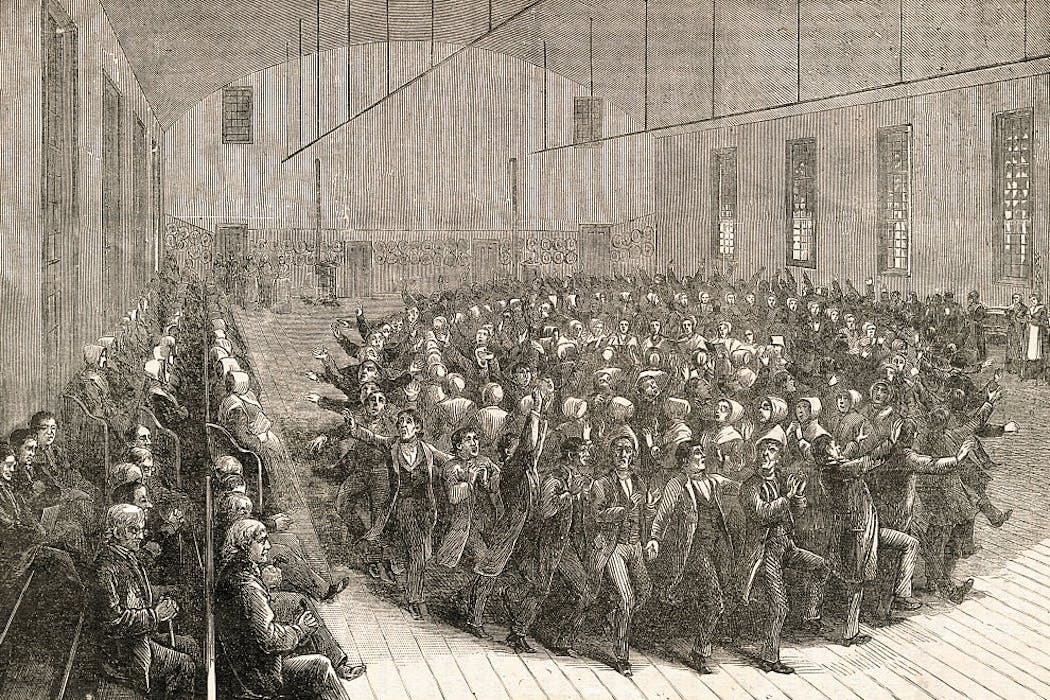

The Global Climate March, held in the early days of COP30, was the most visible moment of this renewed civic presence. Around 70,000 people walked through Belém, bringing together demands for climate, territorial, racial, and economic justice.

Along the march, banners called for protection of the Cerrado and Amazon (Brazilian biomes), land demarcation, an end to illegal mining, defense of the rights of Black and Indigenous women and children, corporate accountability, agrarian reform, an end to fossil fuels, and an end to investments in war. The People’s Summit, whose manifesto was signed by more than 1,000 organizations worldwide, helped to coordinate these voices.

The Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF), a fund designed to create a permanent flow of resources for conserving tropical forests, with more than 50 countries joining, was presented as an ambitious COP30 announcement. The idea is that countries with tropical forests that keep them standing will receive payments per hectare protected or restored.

The Global March united social movements in Belém, November 15, 2025. Photo by Isabela Carvalho, used with permission.

Indigenous leaders welcomed the announcement as recognition of the importance of forests, but responded cautiously. The enthusiasm came with a longstanding demand: that these resources reach communities directly and in ways that respect their governance systems. Concerns about intermediaries and bureaucracy, which often block access to funds, surfaced throughout the conference.

Another key topic, the global roadmap to phase out fossil fuels, did not advance as expected because of disagreements among governments. In response, Brazil announced that it would continue developing its own proposal through the BAM (Belém Action Mechanism), aimed at guiding a just transition to low-carbon economies without leaving behind workers or local communities.

Amid victories and frustrations, the sense is that COP30 was marked by the strong presence of actors rooted in territories rather than offices. The term “systemic change” appeared often to argue for a new paradigm in which development and nature are not treated as separate fields. A message repeated across panels and statements was that real development cannot exist without nature at the center of decision-making.

Debates on fossil fuels, mitigation, adaptation, and finance fell short of what many leaders expected, generating visible frustration. Even so, looking at the process as a whole reveals something meaningful. Voices that were once barely heard occupied the rooms this time, influenced conversations, and took on concrete roles in the flow of the conference. This does not resolve the impasses, but it broadens what is possible for those who participate and those who observe.